The Right-Tail Amputation

discipline, but make it -EV

TLDR: Unless new information has presented itself, deviating from the original ‘game plan’ in trading is not only logically inconsistent, but actually can cause conditional outcomes worse than originally anticipated.

This post is my explanation/extension to an example1 brought up by Lihong that I am borrowing (stealing). While Lihong draws comparisons to the Venture Capital/Private Equity space, I will be connecting this to something more in the trading realm.

Independence Axiom of Utility

Suppose that you have the choice of 2 different lotteries:

I would wager that most of the readers would prefer Lottery A given these two choices (assuming it’s a pure ‘free roll’). BUT, what if, instead of this being a one-shot Bernoulli lottery, this game was played where we first roll a d100 and, if and only if, it is a 1, you can have the choice to take the 10mm guaranteed, or roll a d10 and get 20mm if and only if the d10 comes up with a number from 1-8? Perhaps a lot of you would (irrationally?) pick the option to guarantee the 10mm? Admittedly, it is very tempting to do so, but if you really care so much about that time when you walk away with nothing then you should have picked Lottery B in the first place to begin with otherwise you are literally being logically inconsistent. After-all, you were fine with the extra 0.2% chance you walked away with nothing originally right?

Maybe you’ve taken some “risk” related classes in college, or maybe you went through an internship at one of the trading firms and recall the independence axiom2 from expected utility theory, or maybe you’re hearing about it for the first time here? Regardless, formally speaking, it states that if you prefer one lottery (A) over another (B), then you should also prefer a scenario where you get A with some probability p and a third lottery (C) with probability 1-p over getting B with probability p and C with probability 1-p. In short, your preference between A and B should be independent of any other lottery (C) mixed in. Formally:

And it only takes basic algebra knowledge to see that the (1-p)C cancels out on both sides, thus preserving our preference of A over B.

Let’s define the game in terms of A’, B’, and C now:

And now from this we can clearly see that:

With some substitution, we arrive at:

So if you picked Lottery A, you should be fine rolling the d10 or else you should’ve just picked B to begin with. For whatever reason, this optionality makes people act irrational (from the perspective of being inconsistent).

Real World Trading

Okay at this point, I’m going to pivot into how this temptation to ‘back out’ of a trade for the ‘sure thing’ once the opportunity presents itself. I will first go over ‘locking in profit’ and then similarly ‘locking in EV’. The logic in both is flawed, but I think that it is (more?) understandable to make the ‘locking in EV’ mistake as I think it is an incorrect application of a common interview setup.

‘Lock in Profit’ Mentality

I think that it’s fairly common to hear some [stupid] comment about ‘locking in profits’ where you just sell immediately as soon as you can for a profit. It’s another place where optionality shows up— the “freedom to get out” that somehow makes people do [silly] things. Enter the ‘lock in profit’ mindset. (This mindset is even a horrendous look for an intern to have for what it’s worth.)

I won’t name names, but during one of my onsite interviews for a Chicago OMM, we ran an open-outcry mock market making game. We were trading on the sum of a series of dice rolls with a new d6 revealed periodically. I don’t remember the exact setup, but at one point the fair value, conditioned on previous d6s shown, was 37.

One candidate managed to buy a big chunk for 32 (fantastic fill). The market was bid-on and he dumped his entire position at 34… and seconds later, flashed a 36 bid. The head of trading stopped the exercise immediately.

Let’s pause there. You were long 1,000 at 32, sold at 34, and then re-bought at 36. Congratulations! you just paid 2,000 to end up in the exact same position you started with. Why not just hold your 32s?

Some people are genuinely allergic to inventory. It’s actually financial self-harm dressed up as prudence. The moment they have any exposure, they panic, puke it out for a tiny ‘gain’ and then keep trading. I say it as a ‘gain’ because it’s only a ‘gain’ when marked to the trade print immediately preceding it.

Caveat to ‘Locking in Profit’

This section needs to be said because I know I’m going to get some comment about how you should be willing to give up some amount of EV to reduce variance, but that’s fundamentally different from puking out just to put on a position right after.

(Assume no adverse flow for this example.) Let’s say you’re trading the value of a d6 and you show a market 3.0@4.0 and you get hit (for the non traders reading my blog, this means you just bought for 3.0 dollars). Now suppose that the market is bid-on and now there’s a 3.3 bid shown. Do you hit that and ‘lock-in’ the profit from your buy previously? Based upon what I wrote above you might think that the answer is always NO, but technically that’s not true with a concave utility of wealth function as there should be some amount of EV one should give up to eliminate variance. Under the Arrow-Pratt approximation3 for certainty equivalency (CE) and the assumption of ln(w) utility, we get that:

So unless you have a net worth less than $7.29 you should not ‘lock in profit’ here….

Like I said before—and as you should recall—in the ‘Locking in Profit’ section, remember that the candidate immediately bid above what they sold for so this is a different thing. I digress.

‘Lock in EV’ Mentality

Let’s go back to the example of before where the candidate sold all shares for 34; had the candidate ‘puked’ out for the fair value, that would have been a pretty good trade (so long as he didn’t flash a bid above fair right after lol). BUT this is only because we are able to see the current fair value and trade on this updated value as new information comes out.

This is VERY different from having a thesis that a stock is undervalued, purchasing it, and then immediately selling if your EV is ‘realized’ and it’s trading for what you thought the EV was. Do you see the difference? If we map this over to the sum of d6 example, imagine the contract is on the sum of 10 d6 and the first 3 rolls have all been a 6, the market should be trading around 3.5*7 + 6*3 = 42.5. Does it make sense to be willing to sell at 35 because that was the original EV? Obviously not. The conditional EV has changed from the original EV. For whatever reason people have an easier time seeing this with a d6 rather than with GBM.

Suppose that there is a stock currently trading at 90 dollars and you think over some time period in the future it will have positive drift, such that your fair value is 100 dollars. So you long this stock at 90 and then (shortly after), the stock jumps up to 100 (no new information has presented itself to you). Should you sell? Well ackchyally, you shouldn’t.

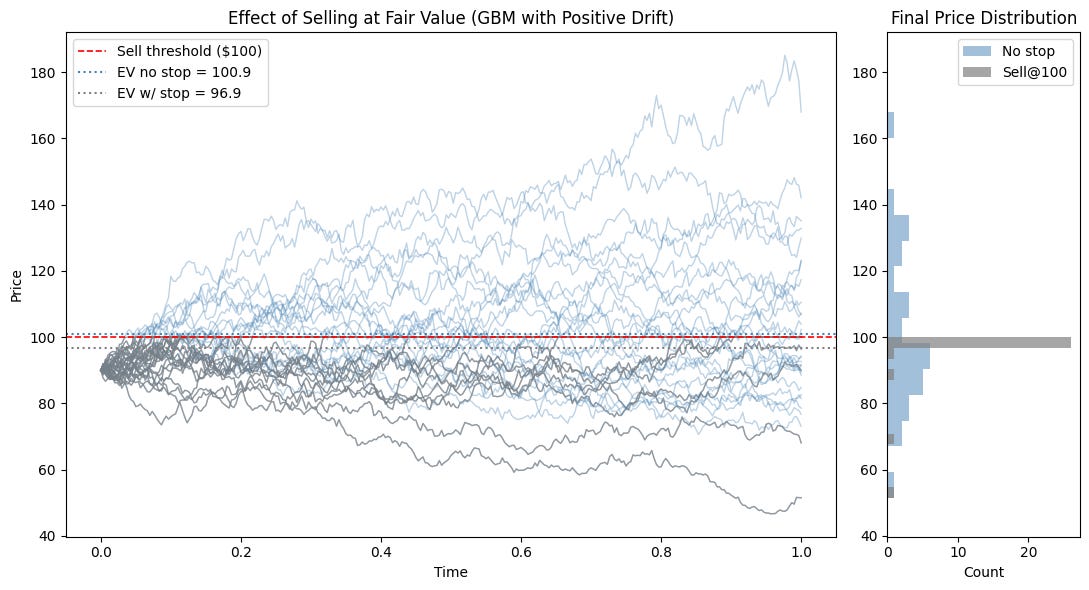

Here’s why: When you thought the stock was worth 100 dollars in expectation, this was the average value across all potential future paths. Within these paths, it includes paths that go above it, as well as ones that go below it, and when you decide to sell as soon as you “realize” your EV, you effectively have made it such that you can only realize paths that are less than, or equal to this EV and thus the EV of this strategy should be strictly lower than the EV of holding despite the EV being “realized”. I think a visual is really helpful here:

As you can see, if we sell as soon as the stock hits 100, we strictly decrease our expected value because the paths with the “favorable variance” we never have a chance to realize, but we guarantee that we will realize all of the downward variance paths.

Prediction Markets (PMs)

Prediction markets are kind of simultaneously GBM and Bernouli markets at the same time. I say this because while ultimately the settlement of the prediction market itself is Bernoulli in nature (it happens or it doesn’t, if we ignore the rare markets with a possible tie settlement), there is typically this random walk of prices and very different trading strategies of top PM traders.

I kid you not when I say that lots of the top Kalshi/Poly traders literally just have a buy low/sell high strategy where they fade every large move. They have no true internal fair value, they just know that people consistently (and predictably) overreact to news so fading these moves is +EV. Perhaps you’ve seen the nothing ever happens meme (which has actually become a recurring market in and of itself on Polymarket)?

These traders also know that the odds on a lot of these markets are just totally subjective and kinda bullshit to be honest. If you know that the true probability of an event is p and you have an existing long position (regardless of the cost basis of said acquired position), it makes sense to lower the position at fair value. However, the ‘fade every large move’ guys will strictly hurt their EV if they sell out of their position as soon as the market moves in their favor because now their PnL should be more skewed towards news reactions that do result in the outcome resolving as they are capping their upside. For them, a strategy of exiting the position (regardless of MTM PnL) after a said time period/number of trades is the logical way to approach this type of trading as they are trading on the time based mean reversion of prices after news, not the actual probability of the event itself.

Recap

Only exercise optionality based on the current state that you are in, not prior expectations; react based upon your updated prior.

The 100$ stock example:

Not counting the opportunity cost of waiting whatever 1.0 time is. 100$ could be re-applied to another bet with better EV. Assuming we have limited capital and a market with good deals.

Your graph also doesn't count that we can re-buy the stock back at 90$ after selling it at 100$. It will not make up for the full EV difference, but not including that opportunity is just misleading.